The Room I Kept

I was a virgin until I was twenty-seven.

I have blamed the Catholic faith. I have blamed my mother. I have blamed fear, repression, the era, the country, the rules. All of that is true, but none of it is complete.

The simpler truth is this: I learned very early that being seen could be dangerous.

My mother had a way of yelling that felt surgical. “Do something—he turned out a faggot. Take him to the whores; they’ll fix him there.” Sometimes it happened in the middle of the night, when sleep was already fragile. She used that word knowing it would stick. A word meant not just to describe, but to condemn. My father would ask her to restrain herself. He didn’t want to look directly at the issue—perhaps because he already knew there was nothing to be done. And so life went on, as it often does in families: with silence standing in for resolution.

Childhood was hard, the way it is for anyone keeping a secret that society has already judged. Being gay was awful then. In many ways, it still is. I’m almost sixty now, and I don’t romanticize any of this.

What I will say is that cruelty did not take root in me.

If anything, it had the opposite effect. It pushed me inward, toward a protected interior space. People often refer to that space as the closet, but I’ve never liked that word. A closet implies fear alone. What I built was closer to a niche—a small inner room where faith lived, not religious faith exactly, but the faith of recognition: I am who I am. I will take care of myself.

Sexuality, when it finally came, came as it was meant to. Late, perhaps—but aligned. I don’t regret that. What I do regret, if regret is the right word, is not having experienced love. Still, a life without romantic love is not an empty one. It sharpens intuition. It deepens compassion. It teaches you to listen closely. There are compensations, even if no one ever taught us to name them that way.

It was during a year abroad, working as an ESL teacher, that Michael entered my life.

I met Michael and his girlfriend while walking my dog. He said he had just returned from the United States and was looking for a place to stay. He was immaculate, his shirt properly pressed, shoes polished, everything precise. I had a spare room. I offered it.

He enrolled in a teacher-training program connected loosely to the American embassy. I was busy with work, enjoying my colleagues, settling into the rhythm of a temporary life. Michael rearranged his room so the bed faced the light. He liked waking up to the sun. He kept a plant by the window. It all felt intentional, almost meditative.

One evening, I came home exhausted. He had just showered and walked into the kitchen, wearing only a towel, asking if I wanted coffee. I noticed the tattoos then—across his chest and arms. They were crude, uneven. - Prison tattoos. I asked about them, casually, without accusation.

He told me he had escaped from prison in Texas.

He said the sentence—six years for possession—had been unfair. He explained it in racial terms, calmly, as though reciting statistics. At the time, I believed him. Or perhaps I chose to. He didn’t seem dangerous. He seemed contained.

A few days later, I came home for a nap. Half asleep, I heard voices. A woman’s voice. Then footsteps. The door to my room opened.

Michael walked in naked, fully erect, and took a pillow from my bed.

I didn’t move. I didn’t speak. I watched.

It wasn’t arousal that froze me. It was recognition. Everything I had been taught to fear—male desire, my own wanting, the body as undeniable fact—was suddenly standing in my room.

They left soon after. I went to the kitchen. I checked the time. Life resumed its schedule.

Twenty years later, I learned who Michael really was.

Beyond being my sexual dream for years, he was also part of what later became known as the Texas Seven.

He returned to the United States to complete his sentence—because I asked him to. I made him see that freedom, if it is to mean anything, must sometimes be regained through repentance. I told him he could explain who he had become, that he had trained as a teacher, and that he could show his credentials. I believed—naively, perhaps—that this might lessen his sentence.

At the time, I valued Michael not only because he described everything I had been taught to negate, but because redirecting his fate away from desire made my feelings feel safer. Less carnal. More ethical.

Isn’t it strange how closets take different shapes? Michael escaped again.

I only learned the full truth a few years ago, when I looked for him, hoping he had made something of his life. What I found was devastating. I had once taken a long nap with a murderer. It remains a beautiful memory, nonetheless.

Michael was executed by lethal injection. He was still a killer.

I don’t write this to absolve him. I don’t write it to condemn him either. I write it because honesty in memory is raw. At the time, he was not a headline. He was a disruption—a collision between the life I had survived and the life I had not lived.

I am grateful that nothing ever happened between us. I understand that whatever tenderness he showed me may have been shaped by prison habits. That is only a guess. Some understandings arrive too late to be useful, but not too late to be true.

And sometimes, when I think of Michael, all I remember is that naked man with a perfect body, hung like a stallion and obsessed with cleanliness, keeping the apartment immaculate. There was something good in him—not enough to save him, not enough to change the course of his life.

I finished my year. I accepted a new contract in Scandinavia. I counted the years.

I remember thinking, around 1998, Michael must be a free man by now.

Today, I think differently. I believe freedom is not granted by governments, sentences, or even forgiveness. It is achieved through self-recognition. Through self-love. Freedom—to be who I am, without apology—has to come from within, not through sex or need.

I write because I now understand that no man will enter my life and become my source of happiness. Nor I his. What changes—what must change—is not the world, but our relationship to ourselves.

No matter how carefully we protect ourselves, the world we live in is penetrable. Influences pass through. People touch us—sometimes through desire, sometimes through fear, sometimes through need.

Michael was one of those people. He touched desire and lust in me, and perhaps that is part of why he returned to prison. Possibly the world outside demanded a self he could not inhabit, while prison, paradoxically, gave him a structure, a role, a definition—even if it was a terrible one. I don’t know. I can only wonder.

At some point, self-preservation stops being a weakness and becomes a strength. Back then, I stood up to Michael’s sexually charged presence. Later, a coworker named Paul. In my teens, a football player. The setting changes, but the exposure stays. We are never sealed off, no matter how carefully we build our inner rooms.

Maturity arrives quietly, not as renunciation, but as discernment. Sexuality, I’ve learned, has very little to do with bodies or with the parts of us that respond to touch. It has to do with love. With mutuality. With consent that goes deeper than desire.

I don’t condemn sex. I enjoy sex. I always have. But whenever I go to bed with a man, I go with love. That has always been my intention. And perhaps that is my vulnerability—to hope, each time, that this might be the one, that love might be met with love.

Often it isn’t. Often it’s just lust. They take what they came for, and they leave.

I am openly gay. I am not in hiding. And yet, for the last ten years, I have chosen not to have sex—not out of fear, not out of shame, but because I know the difference now. I know what sex from lust feels like, and I’ve lived it. What I want to know—what I still hope for—is sex that comes from love.

And maybe that hope, even when unmet, is not a weakness after all. Maybe it is the clearest proof that the self I once protected so carefully was always simple, always whole, and constantly capable of choosing wisely.

In Memory of Michael Anthony Rodriguez (Died by lethal Injection, TX)

May your soul rest in Peace.

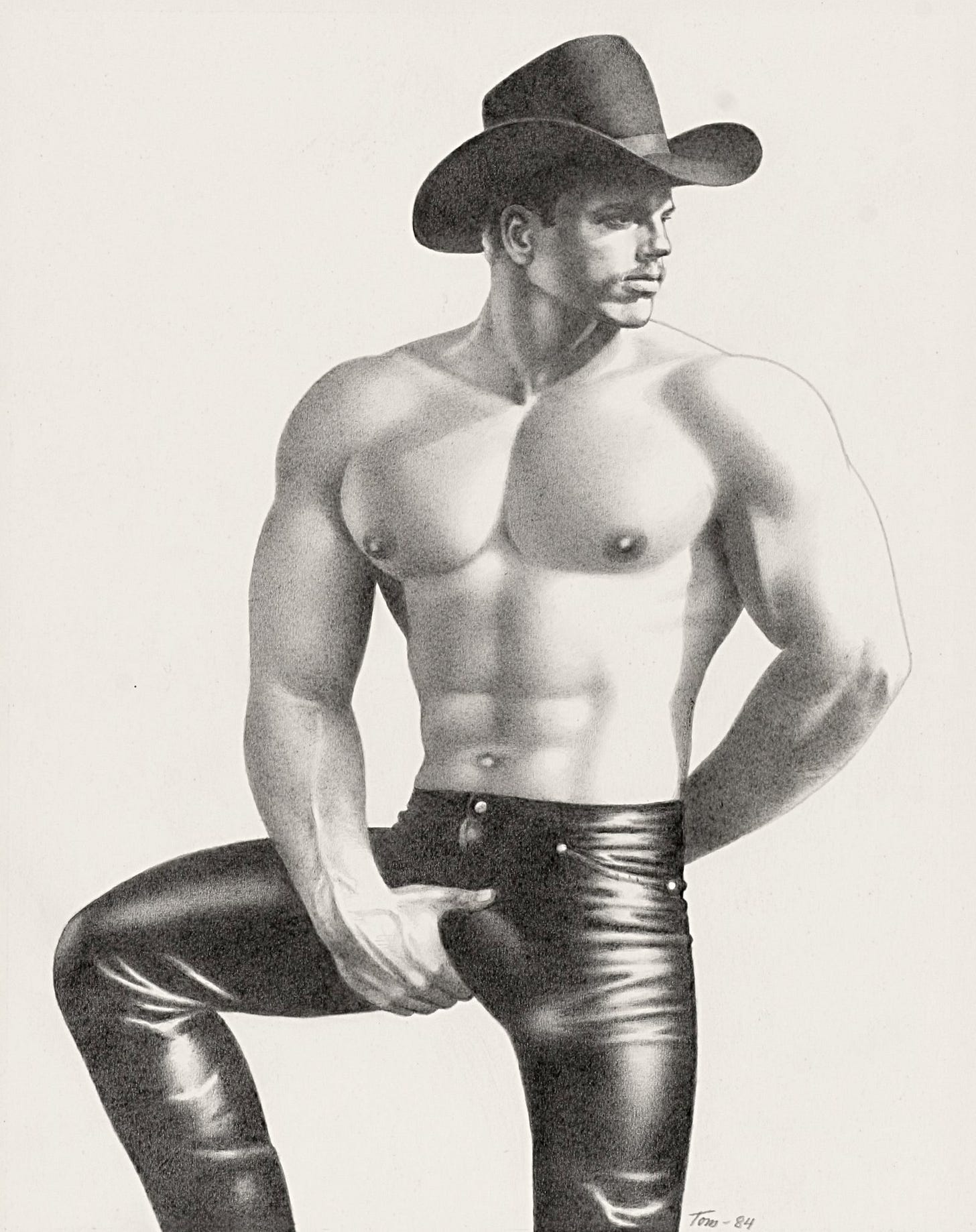

Credits: Picture TOM OF FINLAND

(Touko Valio Laaksonen, Finnish, 1920-1991)

Untitled

1984